This gravitation towards the golden objects and mystery-laden pyramids of Egypt is nothing new. Ancient Romans began collecting and copying Egyptian art soon after Emperor Augustus conquered parts of Northern Africa in 31 BCE. When Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Egypt in 1798 and his soldiers discovered the Rosetta Stone in 1799, Europeans took up the fascination by incorporating ancient Egyptian motifs into everything from ceramics and silver to furniture. Josiah Wedgwood & Sons in England began making red stoneware decorated with black hieroglyphs. Across the pond, Reed & Barton in Massachusetts produced a five-piece “Egyptian Revival” silver-plated tea set, while Boston & Sandwich Glass Company sold glass butter dishes showing the pyramids of Giza. Egyptian ornament was later incorporated into the Art Deco style of the 1920s and 30s.

Howard Carter’s discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 sparked another swell of Egyptomania, which peaked in the United States when 55 objects from the burial toured the country between November 1976 and April 1979. The traveling exhibition was part of President Nixon’s effort to reforge political ties with Egypt. Per a culture clause in the Principles of Relations and Cooperation, the U.S. would help reconstruct Cairo’s opera house, and Egypt would send select King Tut objects to America.

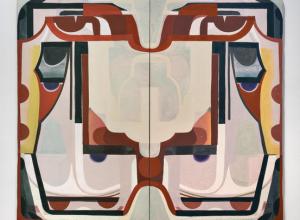

![DEl Kathryn Barton [Australian b. 1972] the more than human love , 2025 Acrylic on French linen 78 3/4 x 137 3/4 inches 200 x 350 cm Framed dimensions: 79 7/8 x 139 inches 203 x 353 cm](/sites/default/files/styles/image_5_column/public/ab15211bartonthe-more-human-lovelg.jpg?itok=wW_Qrve3)

![Ginevra de’ Benci [obverse]. 1474/1478. Leonardo da Vinci. Oil on Panel. Ailsa Mellon Brue Fund, National Gallery of Art.](/sites/default/files/styles/image_5_column/public/ginevradebenciobverse196761a.jpg?itok=hIzdUTaK)