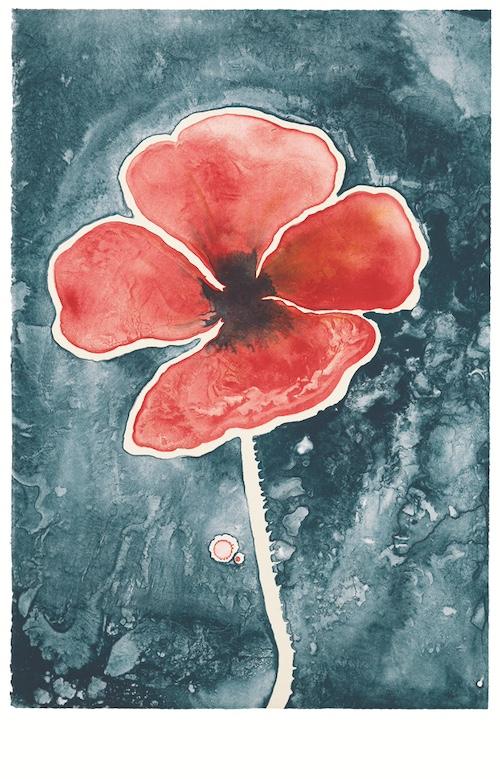

On display are not just sculptures but drawings, paintings, paper folds, masks, redwood doors hand-carved in a curly meander, and baker’s clay sculptures made from flour, water, and salt– a medium she invented for her kids.

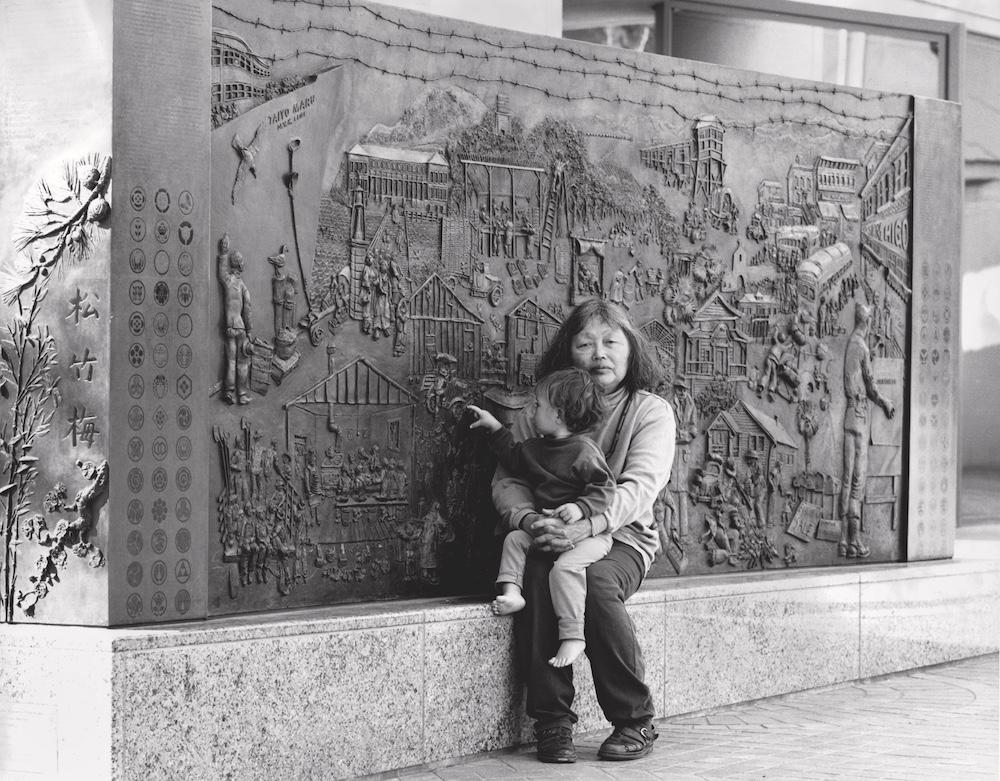

Asawa’s first big lesson in life was when her family was interned during World War II. A teenager at the time, she witnessed the arrest of her father who was taken from their Southern California farm in 1942. It was six years before she saw him again. The rest of the family spent the next five months in Santa Anita where Asawa learned drawing from a pair of Disney illustrators, also imprisoned. From there, the family was shipped to the Rohwer War Relocation Center in Arkansas for a year.

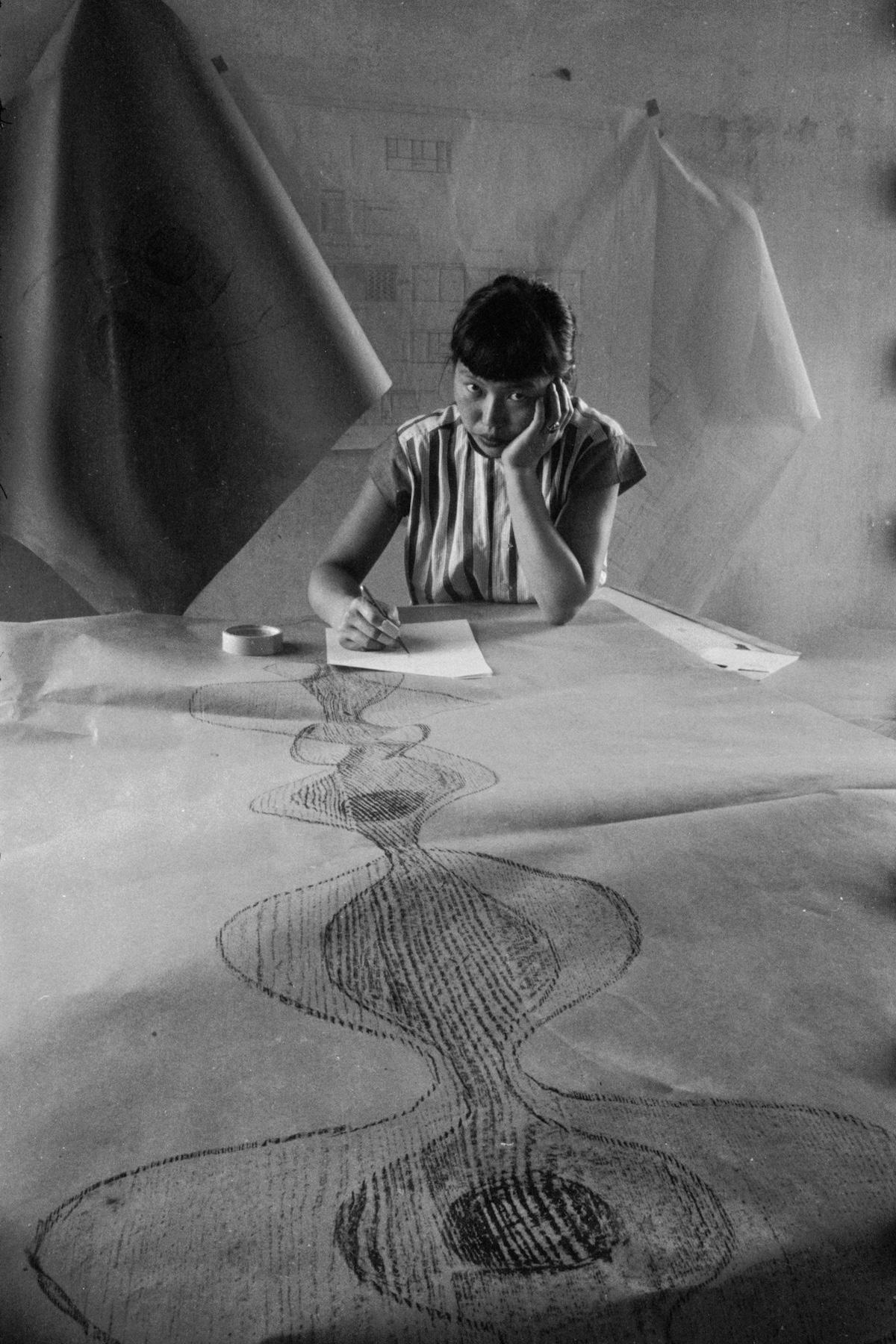

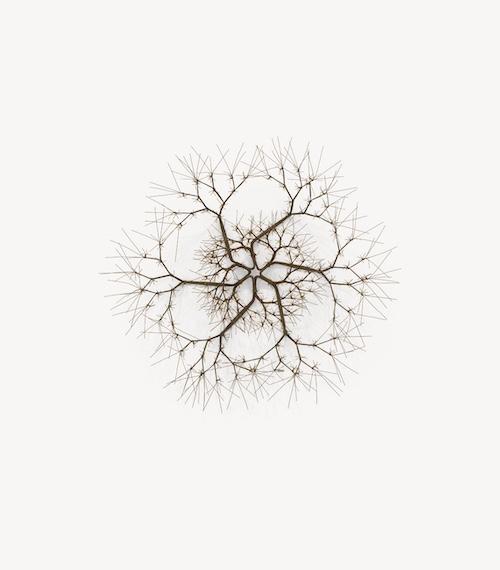

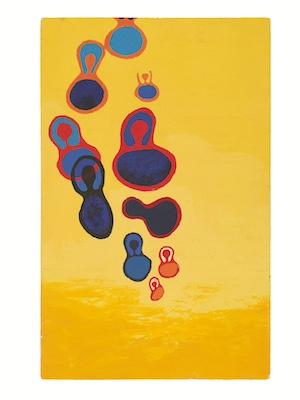

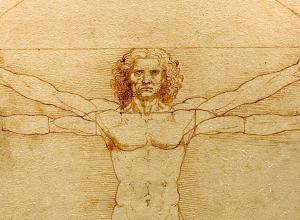

Graduating from the camp school, she intended to become a teacher, but laws prevented Japanese-Americans from doing so. She attended art school instead, at North Carolina’s famed Black Mountain College under the tutelage of celebrated Bauhaus abstract artist and color theoretician Joseph Albers. One of his assignments was to bend a piece of wire, using its line to contour shapes in space. Asawa saw in it the opportunity to create three-dimensional line drawings.