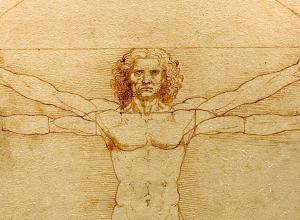

The area being explored is that of the Imperial Forums, a series of distinct but adjoining monumental spaces constructed over approximately two centuries, from 55 BC to AD 112, by Julius Caesar and the emperors Augustus, Vespasian, Domitian, and Trajan. Although each Forum differed in design, they all effectively comprised a large, rectangular, open court, surrounded by colonnades, and dominated by a temple at one end. Used to host ceremonies and to hear legal cases, the Forums also served as showpieces for the regimes and were richly ornamented with statues and colored marbles brought from across the Empire.

The Forums were abandoned by the early Middle Ages, their temples and colonnades collapsing in earthquakes or pulled down and recycled for construction. By the 10th century AD, the central piazzas were given over to agriculture, and a series of rudimentary structures were built atop where there had once been marble pavements. The recently discovered head, as well as those of Dionysus and Augustus, were all found in similar medieval walls, having been crudely reused as building material.