Born around 1457 in Florence, Ginevra was the daughter of the prominent and well-connected Benci family. With a level of wealth second only to the illustrious Medicis, the Bencis amassed a vast collection of literature, entertained and hosted renowned intellectuals and scholars, and acted as patrons to the flourishing Florentine art scene. As such, the Benci children, including Ginevra, were afforded top-rate educations and moved in many influential circles.

In 1474, at the age of 16, Ginevra’s marriage was arranged to Luigi de Bernardo Niccolini– a man 15 years older than her, whom she did not love. It is well attested that Ginevra did not like Luigi. They would spend most of their marriage childless and apart, with Ginevra engaging in multiple courtly affairs throughout her adult life through exchanged letters with paramours and admirers alike. According to one such admirer, Lorenzo de Medici, Ginevra would even later depart the city of Florence– dramatically, by cover of night– to reside at the convent of Le Murate for the remainder of her life.

Before her affairs and her flight from Florence, however, is the mystery of her portrait.

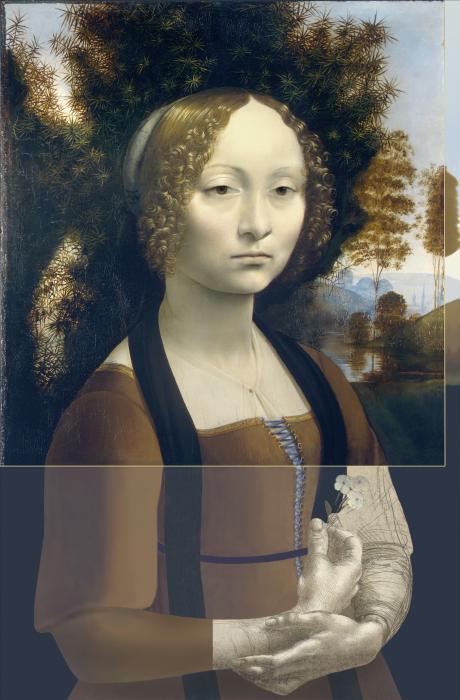

There is no doubt, stylistically and historically, that da Vinci is the artist. Da Vinci is known to have benefitted from the Benci family’s patronage, and the young artist was a friend to Ginevra’s brother, Giovanni. Though, exactly when and why the portrait was commissioned has continued to be a topic of debate amongst art historians.

One theory argues the portrait was commissioned by the Benci family around 1474 to commemorate Ginevra’s engagement. Scholars note that since Ginevra is sitting facing right, she would only have been engaged at the time of the painting’s creation as newlywed portraits typically placed the groom on the left looking right and the bride on the right looking left. Ginevra’s general appearance also points more towards an earlier creation with her soft, round features and glowing, almost pearlescent skin.