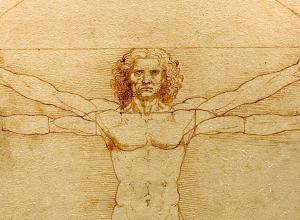

Of course, references to ancient Greece and Rome no longer speak to us in the way they did to French audiences of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Few visitors to the Louvre who stand in front of David’s Oath of the Horatii have much idea who the Horatii were or why the incident resonated with viewers two and a half centuries ago. If anything, one might assume that reverence for the past and the ultimate “dead white male” ancestor culture is what was intended. Quite the contrary—Neoclassicism flourished during the French Revolution, and David himself was a member of the most left-wing radical faction among the revolutionaries, the Jacobins.

Neoclassicism defined itself against the Rococo style that preceded it, which the artists of the late 18th century deemed decadent. In place of Rococo’s extravagances, they championed the simplicity and severity that they believed characterized the Greco-Roman world, especially Republican Rome. In its first iteration at least, Neoclassicism stood for the rationalism of the Enlightenment, justifying and defending it by associating it with the founders of European civilization. The French Revolution grew out of the rationalist world-view promoted by Voltaire and his fellow philosophes, and while its excesses can be certainly be called irrational, the revolutionaries saw themselves as rationalists because of their opposition to the Catholic religion and the tradition-bound reign of the aristocracy. Artistically speaking, the crispness and compositional rigor of Neoclassical painting and drawing connoted rationalism; the rule-breaking expressionism of the Romantics came into vogue after the Revolution was over.

In our own era of irrationalism, the consideration of Neoclassicism in art may be more fraught than ever. Here in the U.S., President Trump has expressed enthusiasm for classicism, going as far as to call for all new federal buildings in the country to be built in a “classical” style and insisting that the sculptures for his projected “Garden of American Heroes” be created in a “realistic” manner, with no “modern or abstract” designs allowed—whatever that means. For an administration that has sought to subvert the Constitutional idea of separation of powers, militated against scientific research, and generally embraced the irrational, any advocacy of classicism, Neo or otherwise, seems highly ironic. At best, it’s an example of poorly understood aesthetics emptied of content; at worst, a cynical misappropriation of a symbolism that runs deep in our history and culture.

To be sure, Neoclassicism and its offshoots served many agendas in their day, not just revolutionary ones. Bourgeois domesticity and antique revivalism were also aided and abetted by Neoclassical art and its associated design styles. Politically speaking, the French Revolution was followed by the Napoleonic era, and many Neoclassical artists went on to glorify the emperor and align him with Greek and Roman antecedents by way of justifying his undemocratic actions.

The U.S. was born during the Neoclassical era, and the rationalism of the Enlightenment pervades our founding documents. The Napoleonic ideal didn’t catch on here. If we take the time today to look closely at Neoclassical art in a place like the Art Institute of Chicago and to appreciate its genius, it would be a good idea to contemplate, at least briefly, the various meanings that classical antiquity has taken on in Europe and America, and to seriously consider the fact that rationalism can be a powerful force for good in both art and life.

*This article originally appeared in Art & Object Magazine's Summer 2025 issue.